Western and Eastern Theories of Salvation

Feb 07, 2021

A comparison of salvation as interpreted by the Western Churches and Eastern Orthodox Church

In this essay I would like to examine Western primarily Augustinian soteriology and compare it to the Eastern Patristic understanding of soteriology. I had originally wrote this in 2019 but only just dug it up and made some edits to it.

Introduction

The most influential scholastic theologians of soteriology in the West are Anselm of Canterbury (1033 to 1109) and John Calvin, both who like most of the Western Church take great influence from Saint Augustine (whether they realize it or not). These two theologians are the progenitors of the two major forms of substitutionary atonement in the West; satisfaction theory and penal substitution theory. They are difficult to distinguish. Satisfaction theory proposes that God’s honor which was tarnished by sin was satisfied by Christ’s death on the Cross. Penal substitution is the later development by John Calvin that only God can repay the debt that is owed to God for the fall of man, therefore Christ had to die for us as penalty for sin. To the Christians of the Patristic age these theories propose an overemphasis of the wrath of God. Christ’s death was indeed necessary to man’s salvation, but the Western Churches (Latin and their Reformed offspring) continued to build doctrine on a doctrine the Eastern Church only considered a part of the picture of man’s salvation.

Ransom Theory of Atonement

Scripturally the ransom theory of atonement comes principally from Mark 10:45 “For even the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.”. In the East, Church Fathers such as St. Gregory of Nyssa and Origen do speak of Christ being a ransom, and even St. Basil’s liturgy speaks of “Christ being a ransom unto death.” This is where the patristic ransom theory of salvation originates, the basis for substitution theory of atonement.

“In order to secure that the ransom in our behalf might be easily accepted by [Satan] who required it, Deity was hidden under the veil of our nature, that so, as with ravenous fish, the hook of the Deity might be gulped down along with the bait of flesh, and thus, life being introduced into the house of death, and light shining in darkness, that which is diametrically opposed to light and life might vanish; for it is not in the nature of darkness to remain when light is present, or of death to exist when life is active. - St. Gregory of Nyssa (The Great Catechism, 24)”.

St. Augustine too speaks of Christ death in such terms of payment and redemption.

“Men were held captive under the devil and served the demons, but they were redeemed from captivity. For they could sell themselves. The Redeemer came, and gave the price; He poured forth his blood and bought the whole world. Do you ask what He bought? See what He gave, and find what He bought. The blood of Christ is the price. How much is it worth? What but the whole world? What but all nations?” - (Enarration on Psalm 95, no. 5)

Even in the liturgy of St. Basil as celebrated Eastern Orthodox Churches it is said that “He gave Himself as ransom to death in which we were held captive, sold under sin. Descending into Hades through the cross, that He might fill all things with Himself, He loosed the bonds of death.”. However, there is controversy as to WHO the ransom is paid to. Theologians such as St. Gregory of Nazianzus object to the idea that the ransom was paid to Satan and instead state that Satan was deceived by God. On the Cross, death was overcome by death, and the deceiver was deceived.

“The Redeemer came and the deceiver was overcome. What did our Redeemer do to our Captor? In payment for us He set the trap, His Cross, with His blood for bait. He [Satan] could indeed shed that blood; but he deserved not to drink it. By shedding the blood of One who was not his debtor, he was forced to release his debtors” (Serm. cxxx, part 2).

But beyond the concept of ransom there is the more prominent theory of recapitulation. Thus, ransom theory is not necessarily opposed to recapitulation, but can be complementary. One thing is clear however. There is no patristic precedence in the first thousand years of Christianity on the ransom being paid to God himself. In some sense, there is not a clear answer because the Fathers collectively understood that salvation was not to be found merely in the Crucifixion and Christ’ death on the cross but also in the Incarnation, the Resurrection, and the Ascension. However, this excessive weight placed on ransom theory of atonement led to further novel developments in theology.

From Ransom Theory to Scholasticism and the Reformation

Beginning with the onset of Western scholasticism (1100s) there was a shift in priority that the Western Church began to place on the figure of Jesus, and the message of the Gospel. In the life of Christ there were three key moments: the Incarnation, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection. Each could not have happened without the prior (with the exception of the Incarnation). In order for the Crucifixion to happen, Christ had to have been Incarnate, and in order for the Resurrection to happen the Crucifixion had to have happened. What the Western Churches seem to have fixated on was the Crucifixion, at the expense of the miracle of the Incarnation and the Resurrection, which will be discussed in the last section.

How does this change in gravity affect how we understand salvation? And how does a difference in understanding change the way we live?

The satisfaction theory of atonement is most associated with Anselm of Canterbury, and co-Doctor of the Roman Catholic Church, Thomas of Aquinas. Anselm sees man having a “debt of honor” to God, which is payed by Christ’ act of obedience to death. Due to the debt, there is a moral imbalance in the universe that can only be satisfied by the sacrifice of a being of infinite goodness, namely Christ the God-man. So the ransom is paid not to Satan, but to God the Father. Following Anselm, Aquinas uses similar language and tone “Christ bore a satisfactory punishment, not for His, but for our sins.”, and this solves two problems, both sins already committed and the sins that will be committed. Though Christ was punished for the sins of mankind at a historic point in time, his passion and death Christ creates an “excess” of merit and grace, articulating the formal beginnings of the idea of the superabundance of merit and the Treasury of Merit. From this Treasury the Catholic Church could then dispense indulgences to remit sins or lessen penance, at first only for the living and later for the dead (15th century).

This sounds very familiar to penal substitution of atonement, but differs in that there is a focus on God being satisfied in the obedience of Christ, rather than satisfied in punishing Christ to enact divine justice. In practice the Catholics have an almost opposite reaction to than the Protestants do because there is almost an unstated notion that he who sins must give reparations to God. We see this most visibly in Western monastic practices, and in the sacrament of penance that requires the penitent to “make reparations and do works of reparation” (Catechism of the Catholic Church on Reconciliation).

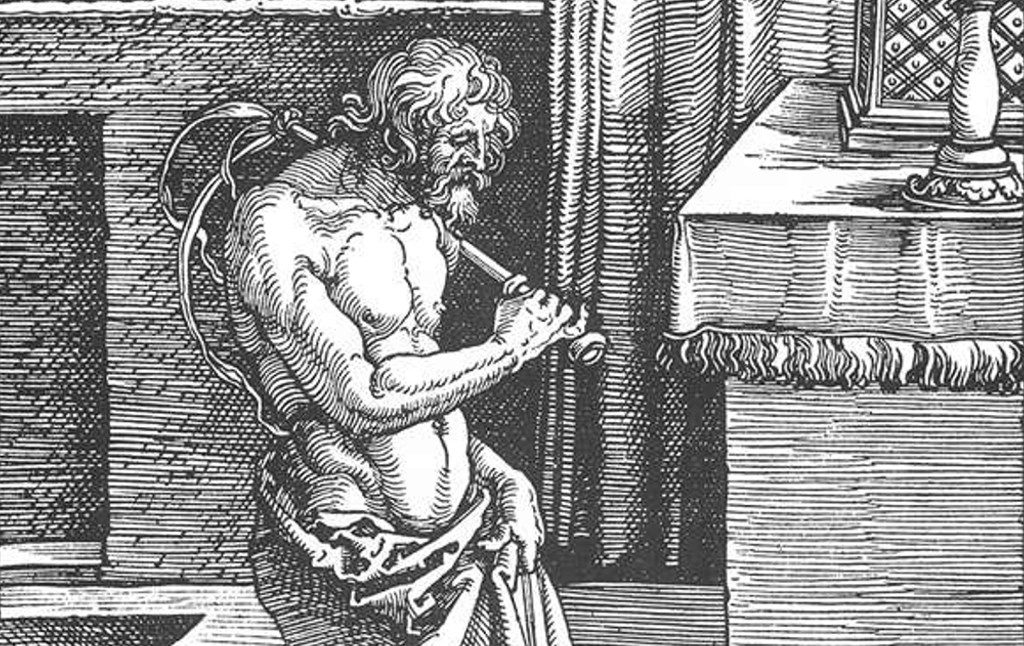

For example, self-flagellation is particular only to Catholic monasteries and convents. To the monasteries of the Eastern Churches, the historic heart of monastic life in Christendom you would not find any mention of flagellation by the Desert Fathers, or Anthony the Great because the monastic tradition and Church Tradition in general did not hold the view that self punishment could act as reparation to God, or even one that it was beneficial. Even in the West, St. John Cassian and St. Benedict who established monasticism did not mention such a practice. Strict ascetism was not done to punish oneself but to allow one’s body and soul be attentive to God. In addition, penance (also named Confession) in the Catholic practice is a very “penal” in the sense that the works one does after confession is almost punishing in nature. One often goes into Confession with a list of one’s sins, and for every sin there is an associated form of punishment, typically in the form of a number of Hail Marys. This falls in line with the idea that it is not enough for one to be repentant but also to be further punished for sinning.

Like the substitutionary theory of atonement, the penal substitution theory of atonement carries with it an emphasis on the Crucifixion and is responsible for Protestant emphasis on “once saved, always saved”, ie unconditional election, and their insistence that salvation is not a process but one that is a singular moment in time (typically profession of faith in Christ). It has its roots in Anselm’s Satisfaction theory, not being fully fleshed out until the Reformers and especially John Calvin during the Reformation in the 16th century. Salvation is seen primarily as a legal exchange (fitting as Calvin was originally trained in criminal law) where man stands guilty before God due to his sin. In order for man to be acquitted, God must punish so somebody has to bear the punishment of sin, namely Christ. Jesus as the spotless lamb died on the Cross as a substitute for sinners, bearing the wrath of God, therefore the condition has been met so mankind can avoid hellfire and God’s wrath. Since that condition of sacrifice to satisfy God’s divine wrath has already been met when Christ died, the work TRULY has been finished, and the only thing left to do is to believe in Christ.

This can unintentionally lead to what many would call license. Of course this does not describe all Protestants in terms of their behavior, but may describe why some Reformed denominations are openly changing the definition of sin if not discounting the seriousness of it. The idea is that if Christ died for me, and I believe in his life and works then whether or not I sin, the promise of the Kingdom of Heaven is unconditional to those that believe. To those that hold unconditional election, Christianity can be reduced to merely a way to avoid hell, and a guaranteed ticket into Heaven. Besides the call to evangelize to as many people as possible, there is a general lack of urgency, and a willingness to turn a blind eye to sin, or to discount it as something already “insured” by Christ’ death. There is no mystery of salvation rather what is left is a simple binary of saved and not saved, just as the theory proposes the yes or no question “Was God’s wrath satisfied?”. The influence of Calvinist doctrine of penal substitution is not restricted to only those who call themselves “Reformed” (Presbyterians) but has spread to virtually all Protestants even if they do not necessarily identify as Calvinist.

If Catholics veer on the extreme end of severity, then Protestants are on the other end of license. Of course, this does not describe actual adherents to either faith as I have met pious and godly people from both traditions. Additionally, in the modern era there is rampant factionalism (conservative/liberal wings) in both confessions so there are rigorous and lenient camps within both. It is rather a general analysis of the spirit of the doctrine, and what it could lead to in historical and modern practices and attitudes.

Recapitulation Theory and Theosis

The East does not deny the truth of the necessity of atonement in man’s salvation, but is bold and joyous in proclaiming that beyond the miracle Passion of Christ, there is the miracle of the Incarnation and the Resurrection. The Church Fathers took for granted that salvation meant avoiding hell but boldly aspired for man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven even on this Earth, for truly the “Kingdom of Heaven is within you” (Luke 17:21). The Church believes that Christ establishes not only the safety net of man in Him but encourages the believer to ascend, as He did, to conquer death and sin as Christ did. The true mission of a Christian is not to avoid hell, but to be deified by participating in God’s energies, through prayer, fasting, and the Holy Mysteries. This Patristic and Eastern theory of salvation has a formal name of the recapitulation theory of salvation, and theosis (divinization) is derived from it. It does not contradict the ransom theory of atonement, but while affirming it redirects ones attention to something of even greater value.

Even before the 4th century with the formalization of theology in the Ecumenical Councils the seeds of this already visible through St. Irenaeus of Lyons.

“Unless it had been God who had freely given salvation, we could never have possessed it securely. And unless man had been joined to God, he could never have partaken in incorruptibility.” - St. Irenaeus (Against Heresies’, 3.18.7)

It is for this reason that the first Ecumenical councils dealt heavily with the nature of Christ, of his Incarnation primarily. The Early Church’ understood that proper Christology was key to understanding how it was that man is saved by God. For example, Christ had to be fully man and fully God in order to save us. If he were a mere man, he could not have saved us for only God can save. More importantly, if He were only God, but not man he could not deify man’s fallen nature, and could not restore man to what Adam once was, sinless and immortal. By participation in man’s nature through the condescension of the Word into the flesh, only then could God heal man’s nature that was disfigured due to the fall. It is not just faith in Christ that saves, but a union with Him and this union is accomplished in the Incarnation. As St. Gregory of Nazianzus as said “what has Not been assumed has not been healed” and as St. Athanasius has said “God became man so that man may be come God”.

There is even an additional event between the Crucifixion and the Resurrection that is often overlooked. In the Harrowing of Hades Christ despoils Hades and preaches “good tidings” to the dead (1 Peter 4:6). Finally in the Resurrection Christ tramples down death by death, glorifying the body even to the point of incorruptibility and immortality, and later in the Ascension He ascends in soul, spirit and body into heaven. He shows himself to be truly the Lord of all and victorious over death. No longer is man’s nature corrupted, but restored to Adam’s nature before the Fall, but even this pales in comparison to the new nature that Christ the God-man calls us all to partake in. The vessel that was once dead can now house the Holy Spirit and can honor and fulfill the image of God by growing in the likeness of God. The disease of sin is cured by the Healer offering His precious Body and His Blood so that we can truly commune with God. Thus, man is given a definitive end in this life, the Kingdom of God, and a means to that end, Christ Himself.

In conclusion, Christ did indeed come to save us from damnation (for God is a judge), but more importantly he came to raise us from the dead, to make us His sons and His co-workers. Thus for Christians, salvation has already happened, is happening, and will happen. Through his love we are saved through baptism, we are being saved by his grace at every moment, and will be saved in the Resurrection to come. Christs life, His Incarnation, his Crucifixion, his Resurrection and his Ascension are all a testament to His love towards mankind, loving us to the point that He allows us to be restored to the heavenly life of Paradise which is union with God, both in this life and in the next.

Further Readings

On the Incarnation - St. Athanasius

Against Heresies - St. Irenaeus

Rock and Sand - Josiah Trenham

Share